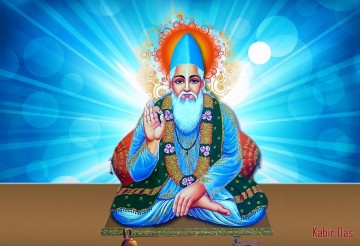

The saint-poet Kabir is one of the most interesting personalities in the history of Indian mysticism. Born near Benaras, or Varanasi, of Muslim parents in 15th century, he became in early life a disciple of the celebrated Hindu ascetic, Ramananda, a great religious reformer and founder of a movement to which millions of Hindus still belong.

Kabir’s Early Life in Varanasi

Kabir’s story is surrounded by contradictory legends that emanate from both Hindu and Islamic sources, which claim him by turns as a Sufi and a Hindu saint. Undoubtedly, his name is of Islamic ancestry, and he is said to be the actual or adopted child of a Muslim weaver of Varanasi, the city in which the chief events of his life took place. The name Kabir means magnificent, great, big. Das means servant of God.

How Kabir Became a Disciple of Ramananda

The boy Kabir, in whom the religious passion was innate, saw in Ramananda his destined teacher; but knew the chances were slight that a Hindu guru would accept a Muslim as a disciple. He, therefore, hid on the steps of the river Ganges, where Ramananda came to bathe often; with the result that the master, coming down to the water, trod upon his body unexpectedly, and exclaimed in his astonishment, “Ram! Ram!”—the name of the incarnation under which he worshipped God. Kabir then declared that he had received the mantra of initiation from Ramananda’s lips, which admitted him to discipleship. In spite of the protests of orthodox Brahmins and Muslims, both equally annoyed by this contempt of theological landmarks, he persisted in his claim.

Ramananda’s Influence on Kabir’s Life and Works

Ramananda appears to have accepted Kabir, and though Muslim legends speak of the famous Sufi Pir, Takki of Jhansi, as Kabir’s master in later life, the Hindu saint is the only human teacher to whom he acknowledges indebtedness in his songs. Ramananda, Kabir’s guru, was a man of wide religious culture who dreamed of reconciling this intense and personal Mohammedan mysticism with the traditional theology of Brahmanism and even Christian faith, and it is one of the outstanding characteristics of Kabir’s genius that he was able to fuse these thoughts into one of his poems.

Was Kabir a Hindu or a Muslim?

Hindus called him Kabir Das (servant of the Infinite), but it is impossible to say whether Kabir was Brahmin or Sufi, Vedantist or Vaishnavite. He is, as he says himself, “at once the child of Allah and of Ram.” Kabir was a hater of religious exclusivism and sought above all things to initiate human beings into liberty as the children of God. Kabir remained the disciple of Ramananda for years, joining in the theological and philosophical arguments which his master held with all the great Mullahs and Brahmins of his day. Thus, he became acquainted with both Hindu and Sufi philosophy.

Kabir Das, a Mystic Poet

A great mystic poet, Kabir Das, is one of the leading spiritual poets in Indian who has given his philosophical ideas to promote the lives of people. His philosophy of oneness in God and Karma as a real Dharma has changed the mind of people towards goodness. His love and devotion towards God fulfill the concept of both Hindu Bhakti and Muslim Sufi.

Kabir’s Songs are His Greatest Teachings

It is by his wonderful songs, the spontaneous expressions of his vision and his love, and not by the didactic teachings associated with his name, that Kabir makes his immortal appeal to the heart. In these poems, a wide range of mystical emotion is brought into play–expressed in homely metaphors and religious symbols drawn without distinction from Hindu and Islamic beliefs. He said that there should be a religion of love and brotherhood among people without any high or low class or caste. Devote and surrender yourself towards the God who has no religion or caste. He always believed in the Karma of life.

Kabir’s Scriptures

The impressive works of Kabir Das are generally the collections of dohas and songs. The total works are seventy-two including some of the important and well known works are Rekhtas, Kabir Bījak, Anurag Sagar, Kabir Bani, Kabir Granthawali, the Suknidhan, Mangal, Vasant, Sabdas, Sakhis and Holy Agams.

Kabir’s impressive works include the Bījak: the most sacred book of the Kabir Panth sect is the Bījak, many passages from which are presented in the Guru Granth Sahib and the Anurag Sagar. In the prestigious Holy Book of the Sikhs, Guru Granth Sahib, 217 songs of Kabir are incorporated (anno 1604). He contributed the most, of all Gurus, in the Guru Granth Sahib.

In a blunt and uncompromising style, the Bījak exhorts its readers to shed their delusions, pretensions, and orthodoxies in favor of a direct experience of truth. It satirizes hypocrisy, greed, and violence, especially among the religious. The Bījak includes three main sections (called Ramainī, Shabda and Sākhī) and a fourth section containing miscellaneous folksongs. Most of Kabir’s material has been popularized through the song form known as Shabda (or pada) and through the aphoristic two-line sākhī (or doha) that serves throughout North India as a vehicle for popular wisdom. In the Anurag Sagar, the story of creation is told to Dharamdas [one of Kabir Saheb’s disciples], and the Maan Sarowaris another collection of teachings of Kabir Saheb from the Dharamdasi branch of the Kabir panth.

Kabirs charisma was so enormous that later poets-mystici were prepared to have their own beautiful songs spread by the name of Kabir, not by their own name.

Kabir Lived a Simple Life

Kabir may or may not have submitted to the traditional education of the Hindu or the Sufi contemplative and never adopted the life of an ascetic. Side-by-side with his interior life of adoration and its artistic expression in music and words, he lived the sane and diligent life of a craftsman. Kabir was a weaver, a simple and unlettered man, who earned his living at the loom. Kabir knew how to combine vision and industry and it was from out of the heart of the common life of a married man and the father of a family that he sang his rapturous lyrics of divine love.

Kabir’s Mystical Poetry Was Rooted in Life and Reality

Kabir’s works corroborate the traditional story of his life. Again and again, he extols the life of home and the value and reality of diurnal existence with its opportunities for love and renunciation. The “simple union” with Divine Reality was independent both of ritual and of bodily austerities; the God whom he proclaimed was “neither in Kaaba nor in Kailash.” Those who sought Him needed not to go far; for He awaited discovery everywhere, more accessible to “the washerwoman and the carpenter” than to the self-righteous holy man.

Therefore, the whole apparatus of piety, Hindu and Muslim alike—the temple and mosque, idol and holy water, scriptures and priests—were denounced by this clear-sighted poet as mere substitutes for reality. As he said, “The Purana and the Koran are mere words.”

The Last Days of Kabir’s Life

Kabir’s Varanasi was the very center of Hindu priestly influence, which made him subject to considerable persecution. There is a well-known legend about a beautiful courtesan who was sent by Brahmins to tempt Kabir’s virtue. Another tale talks of Kabir being brought before the Emperor Sikandar Lodi and charged with claiming the possession of divine powers. He was banished from Varanasi in 1495 when he was nearly 60 years old. Thereafter, he moved about throughout Northern India with his disciples; continuing in exile the life of an apostle and a poet of love. Kabir died at Maghar near Gorakhpur in 1518.

The Legend of Kabir’s Last Rites

A beautiful legend tells us that after Kabir’s death, his Muslim and Hindu disciples disputed the possession of his body—which the Muslims wished to bury; the Hindus, to burn. As they argued together, Kabir appeared before them and told them to lift the shroud and look at that which lay beneath. They did so, and found in place of the corpse a heap of flowers, half of which were buried by the Muslims at Maghar and half carried by the Hindus to the holy city of Varanasi to be burned—a fitting conclusion to a life which had made fragrant the most beautiful doctrines of two great creeds.

Source: Subhamoy Das, Based on Evelyn Underhill’s introduction in Songs of Kabir, translated by Rabindranath Tagore and published by The Macmillan Company, New York (1915)